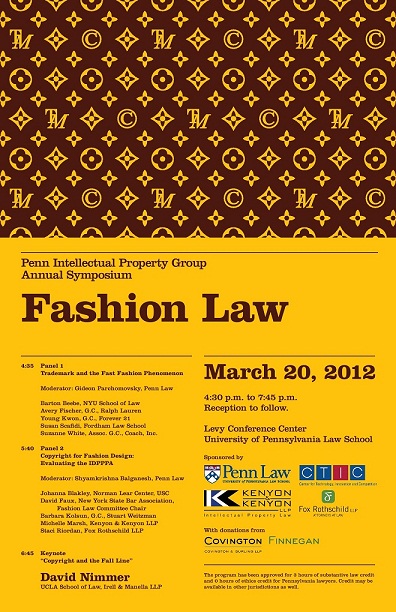

Over the past couple of weeks, the Penn Intellectual Property Group has been the subject of controversy because of a flyer that circulated the law school advertising its much-anticipated Fashion Law symposium by cleverly altering the Louis Vuitton logo. Before I begin this entry, I would like to note that this blog and its opinions do not represent Penn, Penn Law, or PIPG’s positions on the issues. I merely seek to comment on the legal aspects of the controversy.

On February 29, the Director of North American Civil Enforcement for Louis Vuitton Malletier, Michael Pantalony, sent a cease and desist letter to the University of Pennsylvania Law School’s Dean, Michael Fitts, regarding the Fashion Law symposium flyer. Mr. Pantalony identified the group’s advertisement as an “egregious action” that is “not only a serious willful infringement and knowingly dilutes the LV Trademarks, but also may mislead others into thinking that this type of unlawful activity is somehow ‘legal’ or constitutes ‘fair use’ because the Penn Intellectual Property Group is sponsoring a seminar on fashion law and ‘must be experts.’” (Letter from Michael Pantalong, Dir. of Civil Enforcement, N. Am., for Louis Vuitton Malletier, to Dean Michael A. Fitts, U. Pa. L. Sch. (Feb. 29, 2012)).

Over the past couple of weeks, the Penn Intellectual Property Group has been the subject of controversy because of a flyer that circulated the law school advertising its much-anticipated Fashion Law symposium by cleverly altering the Louis Vuitton logo. Before I begin this entry, I would like to note that this blog and its opinions do not represent Penn, Penn Law, or PIPG’s positions on the issues. I merely seek to comment on the legal aspects of the controversy.

On February 29, the Director of North American Civil Enforcement for Louis Vuitton Malletier, Michael Pantalony, sent a cease and desist letter to the University of Pennsylvania Law School’s Dean, Michael Fitts, regarding the Fashion Law symposium flyer. Mr. Pantalony identified the group’s advertisement as an “egregious action” that is “not only a serious willful infringement and knowingly dilutes the LV Trademarks, but also may mislead others into thinking that this type of unlawful activity is somehow ‘legal’ or constitutes ‘fair use’ because the Penn Intellectual Property Group is sponsoring a seminar on fashion law and ‘must be experts.’” (Letter from Michael Pantalong, Dir. of Civil Enforcement, N. Am., for Louis Vuitton Malletier, to Dean Michael A. Fitts, U. Pa. L. Sch. (Feb. 29, 2012)).

On March 2, Robert Firestone, Associate General Counsel for University of Pennsylvania, fired back the school’s response on behalf of the School and Dean Fitts. Mr. Firestone’s letter adamently denies infringement and supports PIPG’s flyer as a non-infringing play on the Louis Vuitton label. The letter argues against infringement claims on two grounds: lack of infringement and lack of dilution. Mr. Firestone explains that there is no infringement because (1) PIPG’s posters are not being used to identify goods and services; (2) Louis Vuitton’s trademarks are likely not “registered in Class 41 to cover educational symposia in intellectual property law issues;” and (3) there is no likelihood of confusion. (Letter from Robert F. Firestone, Assoc. Gen. Counsel to U. Pa. L. Sch., to Michael Pantalony, Dir. of Civil Enforcement, N. Am., for Louis Vuitton Malletier (Mar. 2, 2012)). He supports his denial of lack of dilution by noting that the poster’s artwork is a noncommercial use of the mark and a fair use parody. Id. (“PIPG has not commenced use of the artwork as amark or trade name ...”).

I now consider the validity of one of school’s defenses against Louis Vuitton’s allegations, that being the defense that there is no infringement because there is no likelihood of confusion. There is no likelihood of confusion here because the PIPG poster is advertising an educational symposium and thus is unlikely to be mistaken for a Louis Vuitton luxury product. A multi-factor test may be applied to consider all of the factors contributing to likelihood of confusion, which is especially helpful in instances where the allegedly infringing “good” is noncompeting with the trademark’s product. These factors are:

(1) the degree of similarity between trademark and alleged infringing mark; (2) the strength of the owner’s mark; (3) the price of the goods and other factors indicative of the care and attention expected of consumers when making a purchase; (4) the length of time the defendant has used the mark without evidence of actual confusion arising; (5) the intent of the defendant in adopting the mark; (6) the evidence of actual confusion; (7) whether the goods, though not competing, are marketed through the same channels of trade and advertised through the same media; (8) the extent to which the targets of the parties' sales efforts are the same; (9) the relationship of the goods in the minds of consumers because of the similarity of function; (10) other facts suggesting that the consuming public might expect the prior owner to manufacture a product in the defendant's market, or that he is likely to expand into that market.

A & H Sportswear, Inc. v. Victoria's Secret Stores, Inc., 237 F.3d 198, 211 (3d Cir. 2000) (citing Scott Paper Co. v. Scott’s Liquid Gold, Inc., 589 F.2d 1225, 1229 (3d Cir. 1978)).

On factor (1), Louis Vuitton seems to have a persuasive argument because the marks are similar except Penn Law’s notable TM and © signs. Factors (2) and (3) relate to the strength and integrity of the parent mark as well as the level of sophistication of a potential buyer of the trademarked good. As Mr. Pantalony explained, Louis Vuitton’s mark and brand has a long and rich history in which the brand has “built up a worldwide reputation for its design, innovation, quality and style.” (Letter from Michael Pantalong, Dir. of Civil Enforcement, N. Am., for Louis Vuitton Malletier, to Dean Michael A. Fitts, U. Pa. L. Sch. (Feb. 29, 2012). This effectively means that the mark is likely strong enough to be distinguished from an advertisement that uses a technically different mark and is displayed in a way unrelated to Louis Vuitton’s business. Additionally, because of the high price point for Louis Vuitton goods, the average consumer would be expected to be familiar enough with the mark to distinguish it from the one displayed on the PIPG poster.

Factor (4) and (6) are not useful here as the Symposium’s poster was only displayed for a matter of days when Louis Vuitton challenged it and there has been no evidence of any actual confusion as to the source of the mark from the advertisement; that is students and legal professionals have understood that the source of the poster is the Penn Intellecutal Property Group and not Louis Vuitton. The intent of the students in creating the poster was certainly not to infringe or cause confusion regarding the mark, thus putting factor (5) strongly on the University’s side. Factors (7), (8), (9), and (10) all go to the issue of determining the distance between the markets for the original trademark’s goods and the alleged infringer’s product. Quite clearly, this is the school’s strongest argument for lack of likelihood of confusion. Not only is the school not selling a product of any kind, but PIPG was merely spreading information about its educational symposium. This seems to be a far cry from operating in the marketing channels of an elite luxury good company. Considering these ten factors altogether, Penn Law School and its IP group have a strong argument against Louis Vuitton’s allegation of likelihood of confusion between the club’s clever advertisement and the corporation’s established brand.

It is important to note, that this is just one of the defenses the school may raise against allegations of trademark infringement. In the absence of a denial of likelihood of confusion argument, the school seems quite clearly to have a strong defense from liability because “noncommercial use of a mark” is an explicit exclusion in the federal statute on trademark. 17 U.S.C. § 1125(c)(3)(C) (2006).

Once again, I reiterate this blog merely represents the ideas and opinions of this blogger and do not reflect the opinions of Penn, Penn Law, or Penn IP Group’s on the issue.